88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888 88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Ziryab | |

|---|---|

| زرياب | |

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Abu al-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi (Arabic: أبو الحسن علي بن نافع) c. 789 In the area of modern day Iraq, possibly Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate[1] |

| Died | c. 27 January 857 (aged 67–68) |

| Occupation | linguist, geographer, poet, chemist, musician, singer astronomer, gastronomist, etiquette and fashion advisor |

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

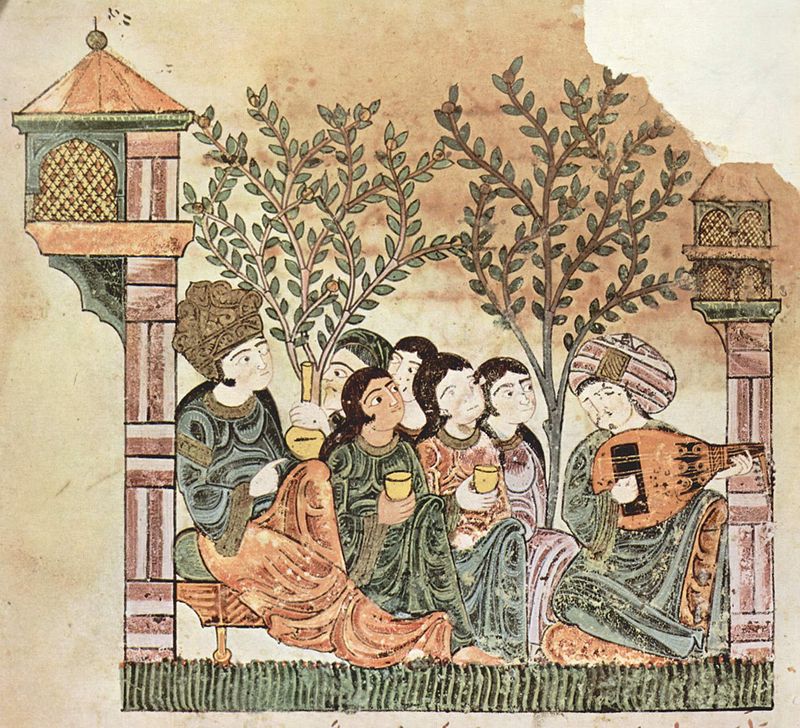

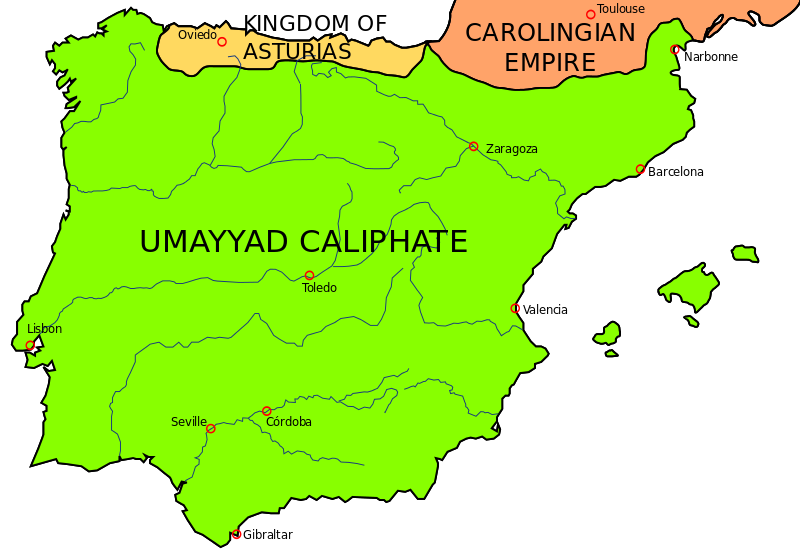

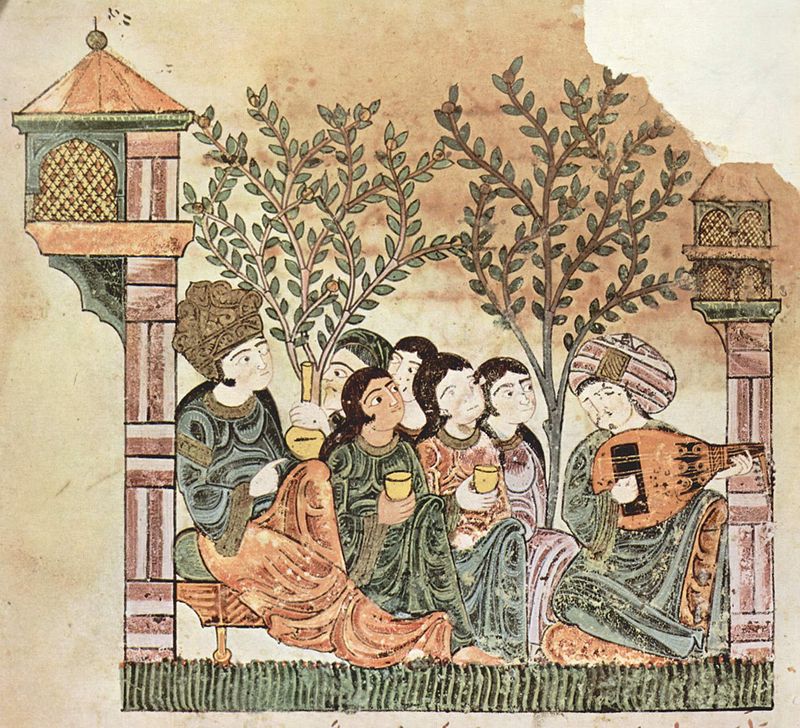

Parallel to the flourishing of music at the eastern centres of Damascus and Baghdad, another important musical centre developed in Spain, first under the survivors of the Umayyad rulers and later under the Berber Almoravids (rulers of North Africa and Spain in the 11th and 12th centuries) and Almohads, who expanded into Spain after the fall of the Almoravids. In Spain, encounter with different cultures stimulated the development of the Andalusian, or Moorish, branch of Islamic music. The most imposing figure in this development is Ziryāb (flourished 9th century), a pupil of Isḥāq al-Mawṣilī, who, because of the jealousy of his teacher, emigrated from Baghdad to Spain. A virtuoso singer and the leading musician at the court of Córdoba, Ziryāb introduced a fifth string to the lute, devised a number of new forms of composition, and developed a variety of new methods of teaching singing in his well-known school of music. Musical activity spread to large towns, and Sevilla (Seville) became a leading centre of musical-instrument manufacture.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Ziryab – The slave who changed society but still remains anonymous in European History

Abul-Hasan Ali Ibn Nafi, nicknamed Ziryab, was Chief Entertainer of the Court of Cordoba in 822AD. He revolutionized medieval music, lifestyle, fashion, hairstyles, furniture and even tableware. He transformed the way people ate, socialized, and relaxed.

Born 789 AD, Ziryab was a significant personality in Islamic culture but remains anonymous in European history in spite of his single-handedness in laying down the groundwork for traditional Spanish music. He was a highly educated North African slave.

He left Baghdad during the reign of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma’mun (d. 833) and moved to Córdoba in southern Iberian Peninsula, where he was accepted as a court musician in the court of Abd ar-Rahman II of the Umayyad Dynasty (822-52).

He was nicknamed Ziryab, probably from a name of a black singing bird in Arabic, a gold hunter or gold digger in Persian, and is also known as Pajaro Negro, meaning blackbird in Spanish.

Zaryab settled in Cordoba in 822 at the court of the then Caliph Abd-Al-Rahman II. His arrival coincided with a new impetus given by Abd-Al-Rahman II to cultural life, leading Andalusia to one of its major flowering periods. In Cordoba, Ziryab found prosperity, recognition of his art and unprecedented fame. He became the court entertainer, with a monthly salary of 200 golden Dinars in addition to many privileges. This promotion gave him a great opportunity to let his talent and creative spirit break free from any boundaries. He not only revolutionized music, but also made significant improvements to lifestyle and fashion.

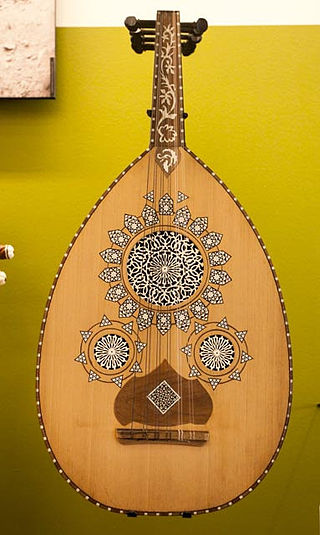

In music, he was the first to introduce the lute (Al-U’d) that later became the Spanish guitar. He is credited, with Al-Kindi, with the addition of the fifth bass string to it and substituted the wooden plectrum for the eagle’s quill.

He was the first to come up with the revolutionary idea of the seasonal change of clothing – not just more or fewer layers, but various styles; starting the trend of wearing brightly coloured silk robes for spring, pure white clothing in the summer and fine furs and quilted gowns for winter’s cold. Ziryab also suggested different clothing for mornings, afternoons and evenings.

Ziryab is known to have invented an early toothpaste, which he popularised throughout Islamic Spain. The exact ingredients of this toothpaste are not currently known, but it was reported to have been both “functional and pleasant to taste.” He also introduced under-arm deodorants and “new short hairstyles leaving the neck, ears and eyebrows free”, as well as shaving for men.

Ziryab, a gastronome extraordinaire, revolutionized all this seemingly feeding frenzy by inventing the multi-course meal, beginning dinner with a soup course, then an entrée and ending it with dessert, a custom that rapidly caught on in the Iberian Peninsula then spread to the rest of Europe and is still used all over the world today.

He concocted many new dishes – his most famous being an asparagus dish. Also, even more importantly, he introduced the drinking glass made from glass or crystal instead of the earthenware, copper, gold, or silver drinking utensils used at the time.

He knew over 10,000 songs by heart and was the finest musician and singer of his day. He introduced the passionate songs, music, and dances of the East into the Iberian Peninsula, which in later centuries, influenced by Gypsy entertainment, evolved into the famed Spanish flamenco.

Ziryab revolutionized the court at Cordoba and made it the stylistic capital of its time. Whether introducing new clothes, styles, foods, hygiene products, or music, Ziryab changed al-Andalusian culture forever. The musical contributions of Ziryab alone are staggering, laying the early groundwork for classic Spanish music. Ziryab transcended music and style and became a revolutionary cultural figure in 8th and 9th century Iberia.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Abu al-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi' (Arabic: أبو الحسن علي ابن نافع, زریاب;[2] c. 789–c. 857[3]), commonly known as Ziryab, was a singer, oud and lute player, composer, poet, and teacher. He lived and worked in what is now Iraq, Northern Africa and Andalusia during the medieval Islamic period. He was also a polymath, with knowledge in astronomy, geography, meteorology, botanics, cosmetics, culinary art, and fashion.

His nickname, "Ziryab", comes from the Persian and Kurdish[4] word for jay-bird زرياب, pronounced "Zaryāb". He was also known as Mirlo ('blackbird') in Spanish.[3] He was active at the Umayyad court of Córdoba in Islamic Iberia. He first achieved fame at the Abbasid court in Baghdad, his birthplace, as a performer and student of the musician and composer Ibrahim al-Mawsili.

Ziryab was a gifted pupil of Ibrahim al-Mawsili in Baghdad, where he got his beginner lessons. He left Baghdad during the reign of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun and moved to Córdoba, where he was accepted as a court musician in the court of Abd ar-Rahman II of the Umayyad Dynasty.

Early life

790 CE: Ziryab was most likely born in Baghdad.[1] According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, he was born around 175 AH/790 into a family of mawali of the caliph al-Mahdi.[5] His ethnic origin is unclear. Based on his appearance and background, different sources suggest him to be of Persian,[6][7][8] Kurdish,[9] Sindi,[10][11] African, or mixed Arab-African descent.[12]

Ziryab was trained in the art of music from a young age. During that time, Baghdad was an important center of music in the Muslim world.[13] The musician Ibrahim al-Mawsili was Ziryab's teacher.[14]

Career

813 CE: Ziryab left Baghdad during the reign of al-Ma'mun some time after the year 813. He then traveled first to Syria and then Ifriqiya (Tunisia) in Kairouan, where he lived at the Aghlabid court of Ziyadat Allah (ruled 816–837).[15]

There are conflicting accounts of why Ziryab left the court. He may have had a falling out with Ziyadat Allah by offending him or some powerful figure with his musical talent.[16] One account recorded by al-Maqqari says that Ziryab inspired the jealousy of his mentor by giving an impressive performance for the caliph Harun al-Rashid (d. 809), with the result that al-Mawsili told him to leave the city.[17][18] Earlier, more reliable sources indicate that he outlived both Harun and his son al-Amin and left after al-Amin's death in 813.[19]

822 CE: He was invited to Al-Andalus by the Umayyad prince, Al-Hakam I (ruled 796–822). He found on arrival in Al-Andalus that prince Al-Hakam I had died, but his son, Abd ar-Rahman II, renewed his father's invitation.[19] He was an intimate companion of the prince. Abd al-Rahman II was a great patron of the arts and Ziryab was given a great deal of freedom. Ziryab settled in Córdoba in what is now Spain with a monthly salary of 200 gold Dinars.[18]

Reputation

Ziryab's career flourished in Al-Andalus. According to Ibn Hayyan, 'Ali Ibn Nafi' was called Blackbird because of his dark complexion, the clarity of his voice, and "the sweetness of his character."[1]

As the Islamic armies conquered more and more territories, their musical culture spread with them, as far as western China in the east and Iberia in the west. After their 8th-century conquest of nearly all of Hispania, which they renamed Al-Andalus, the Muslims were a small minority for quite some time. Muslims were greatly outnumbered by the majority Christians and a smaller community of Jews, who had their own styles of music. Muslims and Arabs introduced new styles of music, and the main cities of Iberia soon became well-known centers for music within the Islamic world.[17] During the 8th and 9th centuries, many musicians and artists from across the Islamic world moved to Iberia. In reputation, Ziryab surpassed them all.[18] Al-Maqqari states in his Nafh al-Tib[20] (Fragrant Breeze): "There never was, either before or after him (Ziryab), a man of his profession who was more generally beloved and admired".

In Cordoba, he was celebrated as the court's aficionado of food, fashion, singing, and music. He introduced standards of excellence in all these fields as well as setting new norms for elegant and noble manners.[18] He established a school of music that trained singers and musicians and which influenced musical performance for at least two generations after him.

He is said to have created a unique and influential style of musical performance, and written songs that were performed in Iberia for generations. He was a great influence on Spanish music, and is considered the founder of the Andalusian music traditions of North Africa.

Ziryab was a "major trendsetter of his time" creating trends in fashion, hairstyles, and hygiene. His students took these trends with them throughout Europe and North Africa.[21] Ziryab also became the example of how a courtier, a person who attended aristocratic courts, should act. According to Ibn Hayyan, in common with erudite men of his time he was well versed in many areas of classical study such as astronomy, history, and geography.

Descendants

According to the main source, Ibn Hayyan, Ziryab had eight sons and two daughters. Five of the sons and both daughters became musicians of some prominence.[18] These children kept their father's music school alive, but the female slave singers he trained also were regarded as reliable sources for his repertoire in the following generation.[19]

Contributions

Music

Ziryab is said to have improved the oud (or Laúd) by adding a fifth pair of strings, and using an eagle's beak or quill instead of a wooden pick. Ziryab also dyed the four strings a color to symbolize the Aristotelian humors, and the fifth string to represent the soul.[17] Ziryab's Baghdadi musical style became very popular in the court of Abd al-Rahman II.[16]

According to al-Tifashi, Ziryab appears to have popularized an early song-sequence, which may have been a precursor to the nawba (originally simply a performer's "turn" to perform for the prince), or Nuba, which is known today as the classical Arabic music of North Africa, though the connections are tenuous at best.

He established one of the first schools of music in Córdoba. This school incorporated both male and female students, who were very popular amongst the aristocracy of the time.[19] According to Ibn Hayyan, Ziryab developed various tests for them. If a student did not have a large vocal capacity, for instance, he would put pieces of wood in their jaw to force them to hold their mouth open. Or he would tie a sash tightly around the waist to make them breathe in a particular way, and he would test incoming students by having them sing as loudly and as long a note as they possibly could to see whether they had lung capacity.

Fashion and hygiene

Ziryab started a vogue by changing clothes according to the weather and season.[18] He suggested different clothing for mornings, afternoons and evenings. Henri Terrasse, a French historian of North Africa, commented that legend attributes winter and summer clothing styles and "the luxurious dress of the Orient" found in Morocco today to Ziryab, but argues that "Without a doubt, a lone man could not achieve this transformation. It is rather a development which shook the Muslim world in general..."[22]

He created a deodorant to get rid of bad odors,[18] promoted morning and evening baths, and emphasized the maintenance of personal hygiene. Ziryab is thought to have invented an early toothpaste, which he popularized throughout Islamic Iberia. The exact ingredients of this toothpaste are unknown, but it was reported to have been both "functional and pleasant to taste".[23]

According to Al-Maqqari, before the arrival of Ziryab, men and women of al-Andalus in the Cordoban court wore their long hair parted in the middle and hung down loose down to the shoulders. Ziryab had his hair cut with bangs down to his eyebrows and straight across his forehead, "new short hairstyles leaving the neck, ears and eyebrows free,".[17] He popularized shaving the face among men and set new haircut trends. Royalty used to wash their hair with rose water, but Ziryab introduced the use of salt and fragrant oils to improve the hair's condition.[24] He is alleged by some[24] to have opened beauty parlors for women of the Cordoban elite. However, this is not supported by the early sources.

Cuisine

Ziryab "revolutionized the local cuisine" by introducing new fruits and vegetables such as asparagus. He insisted that meals should be served on leathern tablecloths in three separate courses consisting of soup, the main course, and dessert.[25] Prior to his time, food was served plainly on platters on bare tables, as was the case with the Romans.

He also introduced the use of crystal as a container for drinks, which was more effective than metal. This claim is supported by accounts of him cutting large crystal goblets.[17] He is also said to have popularized wine drinking.[26]

Notes

- Robert W. Lebling Jr (July–August 2003). "Flight of the Blackbird" (PDF). Saudi Aramco World. 54 (4). Illustrated by Norman MacDonald: 24–33.

- The different aspects of islamic culture: The Spread of Islam throughout the World. UNESCO Publishing. 2011. p. 437. ISBN 9789231041532.

- Gill, John (2008). Andalucia: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-537610-4.

- The Journal of American Folk-lore. Vol. 120. American Folk-lore Society. 2007. p. 314.

- H.G., Farmer; E., Neubauer. ZIRYĀB. Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_sim_8172.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (15 April 2013). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801468711.

The most influential courtier was the musician Ziryab, a Persian, who had held high position in the court at Baghdad

- Monroe, James T. (30 January 2004). Hispano-Arabic poetry: a student anthology. Gorgias Press LLC.

Modernism had been brought from the court of Harun ar-Rashid by Ziryab, the Persian singer who became an arbiter ...

- Scheindlin, R. P.; Barletta, V. (24 August 2017). "Al-Andalus, Poetry of". In Greene, Roland (ed.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691154916.

(...) in the career of Abū al-Ḥassan ʿAlī ibn Nafayni (known as Ziryāb), a 9th-c. ce Iranian polymath who, arriving in Córdoba, used the prestige of his origins to set the court fashions in poetry, music, and manners in accordance with those of Baghdad.

- Gill, John (2008). Andalucia A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780199704514.

- Zuhur, Sherifa (2001). Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Dance, Music, and the Visual Arts of the Middle East. American University in Cairo Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-977-424-607-4.

- Yusuf, Zohra (1988). Rhythms of the Lower Indus: Perspectives on the Music of Sindh. Department of Culture and Tourism, Government of Sindh. pp. 31–32 – via University of Michigan.

- Gioia, Ted (2015). Love Songs: The Hidden History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-935757-4.

- Deboick, Sophia (7 March 2021). "Baghdad - music's fertile territory". The New European. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- Neubauer, Eckhard (2001b). "Ziryāb". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.31002. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription, Wikilibrary access, or UK public library membership required)

- Epstein, Joel (2019). The Language of the Heart. KDP. pp. 234–237. ISBN 978-1070100906.

- Constable, Olivia Remie, ed. (1997), Medieval Iberia, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- Salma Khadra Jayyusi and Manuela Marin (1994), The Legacy of Muslim Spain, p. 117, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09599-3

- Menocal, María Rosa; Raymond P. Scheindlin; Michael Anthony Sells, eds. (2000), The Literature of Al-Andalus, Cambridge University Press

- Davila, Carl (2009), Fixing a Misbegotten Biography: Ziryab in the Mediterranean World, vol. 21, Al-Masaq: Islam in the Medieval Mediterranean

- texte, Ahmad ibn Mohammad al-Makkari al-Maliki al-Maghribi al-Ashʿari Auteur du (1765–1766). Kitab nafh al-tib min ghousn al-Andalous al-ratib wa dzikr waziriha Lisan al-Din ibn al-Khatib, histoire politique et littéraire de l'Espagne, par Ahmad ibn Mohammad al-Makkari al-Maliki al-Maghribi al-Ashʿari, dont la première partie traite de la géographie et de l'histoire de l'Espagne, et la seconde, de la biographie du vizir Lisan al-Din ibn al-Khatib.

- 1001 inventions & awesome facts from Muslim civilization. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. 2012. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4263-1258-8.

- Terrasse, H. (1958) 'Islam d'Espagne' une rencontre de l'Orient et de l'Occident", Librairie Plon, Paris, pp. 52–53.

- Robert W., Lebling Jr. "Flight of the Blackbird". Saudi Aramco World.

- Lebling Jr., Robert W. (July–August 2003), "Flight of the Blackbird", Saudi Aramco World: 24–33, retrieved 28 January 2008

- Susanne Utzt, Sahar Eslah, Martin Carazo Mendez, Christian Twente (30 October 2016). Große Völker 2: Die Araber [Great peoples 2: The Arabs] (Video documentary) (in German). Germany: Terra X via ZDF. Event occurs at 24:05 min. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Gerli, Michael (2003). Medieval Iberia: an encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 850.

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

| Abd ar-Rahman al-Awsat عبد الرحمن الأوسط | |

|---|---|

Silver dirham coined during the reign of Abd ar-Rahman II | |

| 4th Emir of Córdoba | |

| Reign | 21 May 822–852 |

| Predecessor | al-Hakam I |

| Successor | Muhammad I |

| Born | 792 Toledo, Emirate of Córdoba |

| Died | 852 (aged 59–60) Córdoba, Emirate of Córdoba |

| Issue | Muhammad I of Córdoba |

| Dynasty | Umayyad (Marwanid) |

| Father | al-Hakam I |

| Mother | Halawah |

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II, fourth Umayyad ruler of Muslim Spain who enjoyed a reign (822–852) of brilliance and prosperity, the importance of which has been underestimated by some historians.

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II was the grandson of his namesake, founder of the Umayyad dynasty in Spain. His reign was an administrative watershed. As the influence of the ʿAbbā sid Caliphate, then at the peak of its splendour, grew, Córdoba’s administrative system increasingly came into accord with that of Baghdad, the ʿAbbāsid capital. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān carried out a vigorous policy of public works, made additions to the Great Mosque in Córdoba, and patronized poets, musicians, and men of religion. Although palace intrigues surrounded his death in 852, they did not diminish his accomplishments.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Abd ar-Rahman II (Arabic: عبد الرحمن الأوسط; 792–852) was the fourth Umayyad Emir of Córdoba in al-Andalus from 822 until his death in 852.[1] A vigorous and effective frontier warrior, he was also well known as a patron of the arts.

Abd ar-Rahman was born in Toledo in 792. He was the son of Emir al-Hakam I. In his youth he took part in the so-called "massacre of the ditch", when 72 nobles and hundreds of their attendants were massacred at a banquet by order of al-Hakam.

He succeeded his father as Emir of Córdoba in 822 and for 20 years engaged in nearly continuous warfare against Alfonso II of Asturias, whose southward advance he halted. In 825, he had a new city, Murcia, built, and proceeded to settle it with Arab loyalists to ensure stability. In 835, he confronted rebellious citizens of Mérida by having a large internal fortress built. In 837, he suppressed a revolt of Christians and Jews in Toledo with similar measures.[2] He issued a decree by which the Christians were forbidden to seek martyrdom, and he had a Christian synod held to forbid martyrdom.

In 839 or 840, he sent an embassy under al-Ghazal to Constantinople to sign a pact with the Byzantine Empire against the Abbasids.[3] Another embassy was sent which may have either gone to Ireland or Denmark, likely encouraging trade in fur and slaves.[4]

In 844, Abd ar-Rahman repulsed an assault by Vikings who had disembarked in Cádiz, conquered Seville (with the exception of its citadel) and attacked Córdoba itself. Thereafter he constructed a fleet and naval arsenal at Seville to repel future raids.

He responded to William of Septimania's requests of assistance in his struggle against Charles the Bald who had claimed lands William considered to be his.[5]

Abd ar-Rahman was famous for his public building program in Córdoba. He made additions to the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba.[1] A vigorous and effective frontier warrior, he was also well known as a patron of the arts.[6] He was also involved in the execution of the "Martyrs of Córdoba",[7] and was a patron of the great composer Ziryab. He died in 852 in Córdoba.

References

- "'Abd ar-Rahman II". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 17. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- The Inheritance of Rome, Chris Wickham, Penguin Books Ltd. 2009, ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0. p. 341.

- Huici Miranda, Ambrosio (1965). "al-Ghazāl". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 1038. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_2484. OCLC 495469475.

- Graham-Campbell, James (2013). The Viking World. Frances Lincoln Limited Publishers. p. 31.

- El-Hajji, Abderrahman. ""Andalusian Diplomatic Relations with the Franks during the Umayyad period"". Islamic Studies. 6: 27–28.

- Thorne, John (1984). Chambers biographical dictionary. Edinburgh: Chambers. ISBN 0-550-18022-2.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 31.

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Abū l-Mutarraf 'Abd ar-Rahmān ibn al-Hakam (Arabic: أبو المطرف عبد الرحمن بن الحكم), better known as Abder-Rahman II (Toledo, October-November 792 - Córdoba, September 22, 852), son and successor of Alhakén I, was the fourth Umayyad emir of Córdoba from May 25, 822 until his death.

Life

Beginning of his reign

He was thirty years old when he ascended the throne and, like his father and grandfather, had to suppress the claims to the throne of his uncle Abd Allah. He gave himself up to the task of administratively reorganizing Al-Andalus. He tried to present an image of moderation to the Mozarabs and Muslims subjected to the rule of the Arab aristocracy. Aware of the power and influence of the alfaquíes, he ordered the demolition of the Saqunda wine market, near the Cordovan capital, contrary to the precepts of the Koran. Then, as a concession to the mob, he crucified his father's tax policy maker, a Christian the sources call Rabbi.

Yemenis, Muradites and later founder of the Mursiyya

The peace restored in Spain by the emir Abuljatar, by quelling the conflict between the Beledi Arabs and Syrians in the previous century, did not last. The said emir, who began his government measuring everyone equally, soon bowed by the Yemenis, to the detriment of their rivals, the muradis, giving rise to the outbreak of the civil war again with as much or more fierceness than before. The former, that is, the Yemenis, had conquered and established their seat in Yemen, the most flourishing part of southern Arabia, many centuries before our era, subjugating the race of uncertain origin that inhabited that country. The muradies or caisíes were descendants of Ishmael and lived in Hechaz, where Mecca and Medina are located. Both peoples or tribes constituted, so to speak, the first material of the Muslim empire.

The emirate of Abderramán II had just opened, a war broke out in the Tudmir Kora, in the southeast of the peninsula, between the Yemeni and Muradid clans. The spark jumped in Lorca, where the famous battle of al-Musara took place. The war between the Yemenis and Muradids had already lasted seven years and the chora was pacified by the Umayyad general ibm Mu'awiya ibn Hisan, and there is talk of 3,000 dead rebels, including their commander, the Yemeni Abu Samaj.

Abderramán's troops then destroyed the city-refuge of the rebels, Eio, and the Emir decided to transfer the capital of the chora from Orihuela to a new city, Madina Mursiya, founded on Sunday, June 25, 825. Murcia stood on a small elevation on the banks of the Segura River, in order to pacify the territory, promote development and strengthen the authority of the Emirate. General Chabir was the first governor of Murcia.

Andalusi splendor

Abderramán II promoted science, the arts, agriculture and industry. During his reign, the Indo-Arabic numbering system, called position, with a decimal base, was introduced in al-Andalus. Before being proclaimed emir, he started a library that became very numerous, for which he commissioned highly qualified people to bring him the most interesting specimens from the East and those with the greatest contribution to knowledge, thus beginning a good collection of books. He attracted the most illustrious scholars of his time to Córdoba and personally cultivated poetry. His brilliant court was dominated by the figures of the musician Ziryab, the alfaquí Yahya (an intolerant and ambitious religious), the concubine Tarub (who wanted to get the throne for her son Abdalá) and the eunuch Nasr (a muladí).

Abderramán II magnified and showered the city of Córdoba with wealth, surpassing previous emirs in the splendor of his court. According to Eulogio's Memorial:

In 850 (...), the twenty-ninth year of the emirate of Abderraman. The people of the Arabs, magnified in wealth and dignity in Hispanic lands, took hold under a cruel tyranny of almost all Iberia. As for Cordoba, once called Patricia and now named after her settlement, she brought her to the highest concussion, she ennobled her with honors, magnified her with her glory, filled her with riches and embellished her with the influx of all the delights of the world beyond what is possible to believe or say, to the point of overturning, overcoming and overcoming in every worldly pomp.Eulogio de Córdoba: Memorialis sanctorumin: Aldana García (1998), p. 116.

These concise reports coincide with those provided by Ibn Hayyan:

The emir Abderramán ibn Alhakén was the first of the Marwanian caliphs to shine to the monarchy in Al-Andalus, clothed it with the pomp of the majesty and conferred on it reverential character, choosing men for the functions, making visires to perfectly capable people and appointing alcaides to proven paladins; in their days He held correspondence with sovereigns from various countries, erected alcazars, made works, built bridges, brought fresh water to his Alcazar from the tops of the mountains.Ibn Hayyan (2001), p. 171

He increased taxation considerably, and led to better control of income. In his days, the taxes (yibayat) accrued in Al-Andalus acquired a large volume, income from real estate income (haray) increased and records were instituted in the chancelleries of which the correct taxes applied to the population of the country depended, which came to serve as a reference between rulers and subjects. The Anonymous Description of al-Andalus says of Abderramán II:

It was the first omeya that coined in Cordoba, recorded the dirhemes with his name and instituted a bait, to which he put alamines. From the conquest until then the inhabitants of al-Andalus used the dinars and dirhemes that brought from the East. During his reign the tax collection increased, the exactions of the jarachAlcazars, cities and workshops were built; the Christian kings and other places submitted to him.An anonymous description of al-Andalus (1983), p. 149.

The collection reached a million dinars, but the plunder inflicted on the middle and lower classes by forced labor was squandered on courtly luxuries and other extravagances. He built splendid buildings taking advantage of the materials from the Roman period that he plundered everywhere, with the intention of enhancing his government:

He was the first one to make fast buildings and compliments to the bar, using advanced machinery andrevolving all the regions in search of columns, looking for all the instruments of al-Andalus and

taking them to the caliphal residence of Cordoba, so that all famous factory there was construction and design of his.Ibn Hayyan (2001), p. 182.

Abd al-Rahman ordered the expansion of the aljama mosque in Córdoba, placing Nasr and Masrur, the main eunuchs, in charge of the work, and the work was supervised by Muhammad ibn Ziyad, the qadi of Córdoba. Abder-Rahman's wives and concubines also built mosques which bear their names and are known by them, such as the Tarub Mosque, the Fahr Mosque, the Achchifa Mosque, the Mut'ah Mosque, and many other similar ones, and they competed in good works and alms in Córdoba and in their district. Abderramán surrounded himself with scholars, alfaquíes, scholars and courtly poets, whom he splendidly entertained, especially the alfaquíes and muftíes. To Ziryab, a famous musician whom he sent to come from Baghdad, he made great concessions and assigned him generous emoluments, since he received two hundred cash dinars a month, and his name came on the payroll immediately after the viziers. The emir extended to his sons successively desirable allowances, giving them fixed salaries and magnificent territorial concessions, so that they would not burden their father in his emoluments in the slightest, paying each of the three, Ubaydallah, Ja'far and Yahya., twenty dinars per month, in addition to the regular bonuses.

Foreign Policy

In order to maintain the luxurious lifestyle of his court and suppress the discontent caused by the despotic regime, the emir maintained his father's militaristic policy, increasing the number of foreign armed forces, loyal only to him, who They did not mix with the population. Likewise, skillful work was carried out to build fortresses (ribat) that would give rise to towns such as Calatrava (Qala'at ar-Ríbat).

Almost every year there were attacks against the Christians and in some cases three were even unleashed. The majority was directed against Álava and, especially, Galicia, which was the most vulnerable region of the Kingdom of Asturias. Despite this, there were also attacks against Osona (Vich), Barcelona, Gerona and even Narbona in the expeditions of the years 828, 840 and 850.

In May 843, Musa ibn Musa, head of the Banu Qasi family, led an insurrection against them, being helped in it by García I Íñiguez, king of Pamplona, with whom he was related. After the uprising was crushed, he attacked the lands of Pamplona, defeating García Íñiguez and Musa.

On November 11, 844, he prepared a contingent to face the Vikings who had conquered and sacked Seville a month earlier. The pitched battle took place on the grounds of Tablada, with catastrophic results for the invaders, who suffered a thousand casualties; another four hundred were taken prisoner and executed and some thirty ships were destroyed, the hostages being released. Over time, the small number of survivors converted to Islam, settling as farmers in the area of Coria del Río, Carmona and Morón de la Frontera. New Norman raids were given in the years 859, 966 and 971, the latter being frustrated and the Viking fleet totally annihilated.

The martyrs of Córdoba

Regarding the Hispanic population, they continued to regard their Muslim masters as invading despots, a feeling accentuated by reasons such as schizophrenia derived from the rapidity of conversions to Islam, mixed marriages, economic causes such as the new tax system (the loss of productive base), and the loss of power of the Christian religion before the Muslims. The pressures to abandon Latin and Romance in favor of Arabic became unbearable for this small group of followers of Eulogio de Córdoba. The Mozarabic problem broke out again when, in the course of a conversation, a Cordovan priest named Perfecto declared that Muhammad was a false prophet, in addition to insulting him. Perfecto was brought before the qadi, sentenced to death, and beheaded on April 18, 850 before a rousing mob. The bloody event, although it had several precedents, on this occasion produced a whole chain reaction in the jaded Mozarabic people: the famous episode of the Martyrs of Córdoba, in which 48 prominent Christians deliberately defied the laws against blasphemy, apostasy and Christian proselytism, knowing that death awaited them. Despite this, the pressures and cruel persecution in this period led to numerous conversions to Islam.

Shortly before dying in 852, Abderramán managed to get a council of Mozarabic bishops, chaired by Metropolitan Recafredo of Seville, to forbid from the pulpits that his faithful perform similar acts in the future, without condemning the conduct of the martyrs who had challenged to Islamic power. By not formally repudiating such acts, martyrdoms continued for a few years, until the movement died out in 859.

Portrait of the emir

Ibn Idhari left us this portrait of Abderramán II:

...was very dark and eagle nose. He had his eyes big and black and sharp eyes. It was tall and corpulent and had very accented the nasogenian groove of the upper lip, where the mustaches were separated. His beard was very long, and much use of henneand ketem.

Ramón Menéndez Pidal says of him:

...This prince, except his descendant al-Hakam II, was, of course, the most cult of all the Hispanic-Omeya emirs. It was very given to literature, philosophy, science, music and, above all, poetry, because it had great ease to compose verses. He was interested in the hidden sciences, astrology and interpretation of dreams. He wrote a book entitled Al-Andalus anals. After consolidating his power, he devoted himself to his pleasures without any brake.

Family and children

The Emir Abderramán was madly a womanizer, and never took anyone who was not a virgin, even though she surpassed the women of his time in beauty and excellence, his taste, inclination and dedication to them being excessive, as well as the number in which he had them and the passion of which he made them the object. He had several favorites among his concubines, who dominated his heart and conquered his passion. Among all of them, he ended up with his love called Tarub, mother of his son Abdallah.

To keep them happy, he gave them splendid gifts. To his concubine al-Shifá (Salud) he gave a very valuable pearl necklace called the Dragon, formerly the property of Zobeida, the wife of Harun al-Rashid, which he had bought for ten thousand dinars, which seemed excessive to one of his closest viziers.

The almost proverbial amatory capacity of Abderramán II resulted in a large offspring, which the sources estimate with admiration at the extraordinary number of 87 children, 45 of them male. He was succeeded by Mohamed I.

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

No comments:

Post a Comment